After all our brainstorming and character building fun, now it’s time to begin adding structure to your story. This is where you weld into place the foundation and girders that will hold up your storyscraper.

When I first began writing, I didn’t think about structure at all. I had a story to tell, and I told it. As I learned more about Story and the writing craft, I realized there were some things I’d done involuntarily. These things are inherently part of storytelling — keeping the reader involved in a story, speeding up the pacing or slowing it down, throwing more rocks at your character stuck up in that tree. But for awhile, I remember being terribly confused. I suddenly knew why I’d done certain things, but then the how began to waiver. If I’d done something naturally, how could I force it to happen now?

Trust the magic. It’s there. You’ve been mixing a potion from the very start of storybuilding. Adding a framework for the story to hang onto will not damage the magic. On the contrary, it will give it a place to shine.

Knowing the structure of the story helps you guess the length too. Say you have a really big “candybar scene” already in mind, but you have no idea how far into the story that scene will play out. Is it in the first third? The last third? Somewhere in the middle? Thinking about structure — and specifically the hero’s journey — will help you figure out in which “Act” the scene lies.

The level of detail you define at this point of Storybuilding is entirely up to you and the story you’re writing. Don’t be surprised if one story wants more work than others — my process changes a little with each story I write. I’ve known people who plotted out to great detail with pages and pages of outline and scene details. I’ve also known people who only have a vague idea of the ending and that’s what they’re writing toward.

The whole point of this exercise is to get a story to the place where you can successfully begin writing. By “successfully” I mean that you’re setting yourself up to FINISH THE BOOK. In the end, that’s the only victory. Do whatever you need to do to finish the book. Plot a lot — plot only a little. Write up detailed character sketches — or just a few emotional letters. Whatever you need to. Finish. The. Book. You can plaster over holes, demo entire rooms or floors of the storyscraper if you need to, LATER. You can’t see enough of the Story structure and how it fits into the skyline you envisioned until you finish the first draft. Renovation Nightmares will begin later.

If you at least know the ending of the book, then you have a target to shoot for. If you know the major inciting incident that sets the story in motion, then you know how to write the first 100-120 pages of the book. If you can get a few additional key scenes or surprises laid out in your mind, then you’ve got something to write to in the middle. How much more detail you add at this point is entirely up to you.

Personally, how much work I do depends on the length of the story. Ironically, very short and very long pieces take about the same amount of work. In a short story, you need to choose the scenes very, very carefully. A good short story is still going to have a character changing in some memorable way, and the few precious words must reflect those changes quickly. A long (e.g. 100K or more) story has a lot of Deadly Middle Ground to conquer. If I don’t have a few key turning points already identified, I’m going to get stuck halfway over the mountain, and that’s not a good place to be.

There are a ton of great Hero’s Journey links available on the internet. Also check out our character clinic and Left Behind & Loving It categories; my friend Jenna wrote up a great post about how she uses the hero’s journey. I refer back to Vogler’s The Writer’s Journey constantly.

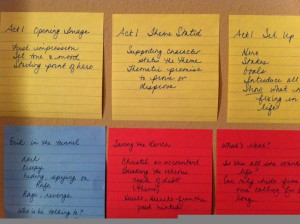

Minimally, I like to know the following journey points of a story before I begin writing (and why). I do a lot of this brainstorming on paper, and then when I know the rough idea of the “scene,” I write out a card for it. One card may spawn another idea, so I jot that down. Think about reactions – you can get another card or so for each main POV character after a turning point scene. How did Victor feel when THIS happened? What’s he going to do now?

- Ordinary World: this helps me figure out how to start the book in the right place. Note that you still have to have ACTION happening here. Characters in the shower, waking up from a dream, etc. are boring

- Inciting Incident: this is the Big Bang that sets your story universe into motion. It’s the event that sets your hero’s feet onto the yellow brick road of your journey.

- Crossing the Threshold: this scene helps me know that Act I is finished and I’m moving into the middle. The first Act should be roughly 100-120 pages (in a 400 page book). If my character takes the first step on the main journey — and I only have 50 pages — then this is going to be a very short novel. Maybe that’s okay – or maybe I need more details.

- Midpoint Shakeup: Okay, I lied, this isn’t part of the hero’s journey, not exactly. But I love to have a big major event in the midpoint of the story. It’s the candybar I’m writing toward that helps me get the next 100-150 pages.

- Approaching the Innermost Cave, the Dark Moment: there comes a time when the hero believes all is lost, the journey is hopeless, the battle will never be won. This is signaling the end of Act II. Even though I’m on the downhill slide at this point, I always get bogged down around 275-320 pages of a book. It’s like the bleak emotions begin to take their toll on me — and I find myself in my own dark moment. This is where I begin to wonder if I’m going to be able to pull the story off. This would be a really really bad time for me to read a negative review or allow any harsh words to inflict any damage on my writer’s psyche. This is a whole other post — but protect the writing. Protect yourself. “Having a thick skin” does not mean that you need to shovel other people’s caca with a smile!

- The Climax(es): Ah, the showdown begins. The last 100 pages–once they get rolling–should just fly. Now your hero goes to battle. You throw every surprise and horror at him/her that you can think of. If you’re really doing good, you’ll write them so far into a dark dead-end alley that even YOU won’t have any idea how to get them out. Yes, this still happens, even if you “plot” the story. Let the magic happen.

- Resolution and Return: in the last 20 pages or so, tie up all loose ends, decide how your character is going to live out the rest of his life, grieve for the fallen, and soak in the victory. I don’t always do a ton of plotting for this stage — unless there’s a book that follows. Then I need to make sure that the elements I need to bridge into the next book are present and make sense.

Now you may feel as exhausted as your characters, but I promise, nothing, absolutely NOTHING, compares to the rush you’ll feel when you type:

The End.

P.S. If spreadsheets don’t scare the crap out of you, you may find these helpful. These are filled out for the Maya thriller. The character rows are the major players that I needed to track through the story, even if they didn’t have a POV. Note that I didn’t do this much plotting before the first draft — this level of detail came during Revision Xibalba.

The Bloodgate Codex spreadsheets

If you’re interested in the blank templates, I’ll post them later — I don’t have them handy on this computer.